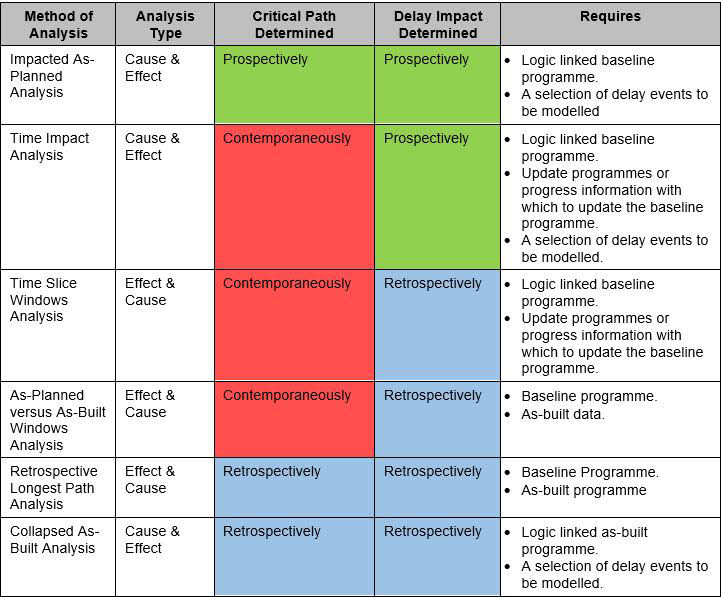

Delay Analysis is a contentious issue in claims arising out of construction projects. Often time, there is an argument over the correct or more correct analysis method for delay analysis. The Society of Construction Law Delay and Disruption Protocol (‘SCL Protocol’) sets out the following differing methods of delay analysis that can be used to analyze the impact of a delay event to the critical path of a construction program:

On 17 October 2022, the High Court handed down its decision in Thomas Barnes & Sons plc v Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council [2022] EWHC 2598 (TCC), which related to the construction of a bus station in Blackburn.

The claimant, Thomas Barnes & Sons plc (in administration) (‘Thomas Barnes’) was the contractor employed by a local Council, with the project suffering significant costs increases and delay. The Council purported to terminate Thomas Barnes’ contract and engage another contractor to complete the works. Soon after, Thomas Barnes went into administration, with the administrators subsequently seeking approximately £1.7 million in damages. This included an entitlement to prolongation and delay-related damages, which led the Judge to provide some discussion on the differing forms of expert delay analysis relied on by the parties.

In Thomas Barnes, the Judge noted that it would be wrong to place too much importance as to whether a particular method of delay analysis had been strictly followed, stating that:

‘The SCL Protocol itself discourages such an approach. It states in the introduction that:

(a) its objective is to provide useful guidance.

(b) it is not intended to be a contract document nor to be a statement of the law;

(c) its aim is to be consistent with good practice rather than to be a benchmark of best practice; and

(d) its recommendations should be applied with common sense. It states under paragraph 11.2 that “irrespective of which method of delay analysis is deployed, there is an overriding objective of ensuring that the conclusions derived from that analysis are sound from a commonsense perspective”.

Thus, it would be wrong to proceed on the basis that, because the SCL Protocol identifies six commonly used methods of delay analysis, an expert is only allowed to choose one such method and any deviation from that stated approach renders their opinion fundamentally unreliable. It must be borne in mind that the common objective of each is to enable the assessment of the impact of any delay to practical completion caused by particular items on the critical path to completion. However, I do accept that if an expert selects a method which is manifestly inappropriate for the particular case or deviates materially from the method which he has said he is following, without providing any, or any proper, explanation, that can be a material consideration in deciding how much weight to place on the opinions expressed by the expert.’

Especially when part of the claim centres around an extension of time, expert delay analysis is commonly relied on in both adjudication or litigation to prove or disprove a claim. In light of the Judge’s comments in Thomas Barnes, it is not a requirement for a particular method to be strictly followed. However, delay experts should be conscious of the impact that a deviation from the stated method used or the use of an inappropriate method will have on the weight of their evidence without a reasonable explanation

Other observations from Thomas Barnes

Traditional approaches to the main cause of delay have been the ‘dominant cause’ approach, focusing on the main cause of the delay, or alternatively, the ‘first in time’ approach, focusing on the event that occurs first. However, the Judge found that concurrent delays had occurred, even though there appeared to be a dominant delay, separate to one that occurred first. In this instance, the Judge made a finding that ‘depending upon the precise wording of the contract a contractor is probably entitled to an extension of time if the event relied upon was an effective cause of delay even if there was another concurrent cause of the same delay in respect of which the contractor was contractually responsible’. However, the Judge noted that despite being entitled to an extension of time for a dominant cause delay, the Contractor would not be entitled to costs for loss and expense where a separate concurrent delay occurred for which the contractor was contractually responsible.

Leave a Reply